D-3.8 Stormwater Site Retention Systems

Water evaporates from lakes, rivers, and oceans. It then becomes water vapour and forms clouds. It falls to the earth as precipitation and then evaporates again. This hydrological cycle never stops. Water keeps moving and changing phases from solid to liquid to gas, repeatedly. This process is described as the natural water balance. Stormwater is runoff generated by human development. It is created when land development alters the natural water balance and flow.

When vegetation and soils are replaced with roads and buildings, less rainfall infiltrates into the ground, less gets taken up by vegetation, and more becomes surface runoff. The biggest increments of change to the water balance in general — to the surface runoff component — occur when natural land is cleared and paved over. Environment Canada has estimated that urbanization of a natural drainage basin can increase stormwater runoff by 400% or more.

Until recently, the traditional approach to drainage has been to remove runoff as quickly as possible from developed areas. As a result, traditional urban design is very efficient in collecting, concentrating, conveying, and discharging stormwater to receiving waters. Runoff volume increases in proportion to impervious area (hard, non-absorbent surfaces). Traditional ditch and pipe systems have been designed to remove runoff from impervious surfaces as quickly as possible and deliver it to receiving waters. The resulting storm water arrives at the receiving waters much faster and in greater volumes than under natural conditions. This traditional grey infrastructure approach can cause flooding, loss of aquatic habitat, and water pollution in downstream receiving waters. Modern stormwater source control practices provide rainwater capture to reduce runoff volumes.

Stormwater Management Strategy

A stormwater management strategy seeks to mitigate the impacts of increased urban runoff and stormwater pollution by managing it as close to its source as possible.

The Local Government Act sets out specific provisions for planning, regulation, development approval, and servicing provisions applicable to storm water management, such as:

- Prohibition of pollution

- Soil deposit and removal (erosion control)

- Zoning

- Environmental policies

- Runoff control

- Landscaping

- Development permit areas

- Subdivision servicing requirements

In addition to the above, other municipal stormwater management powers can be found in provisions dealing with:

- Building regulations

- Contaminated sites

- Development cost charges

- Ditches and drainage

- Dikes

- Development works agreements

- Flood protection

- Farming

- Highways

- Improvement districts and specified areas

- Park land

- Regional district services

- Sewage systems

- Subdivision

- Temporary commercial and industrial use

- Tree cutting

- Utilities

- Water

- Waste management.

To achieve performance targets for rainfall capture, runoff control, and flood risk management, the targets must be translated into achievable design guidelines that developers and local government staff can understand and apply at the site level.

Reducing runoff volume is the key to achieving performance targets for rainfall capture. The following volume reduction strategies should be applied:

- Minimize the disturbance of natural soils and vegetation.

- Apply absorbent landscaping.

- Implement stormwater source control practices to capture runoff from impervious surfaces.

Minimize the Disturbance of Natural Soils and Vegetation

At the land use planning and site design levels, it is important to identify and preserve the natural areas that are most important to maintaining the natural water balance, such as wetlands, natural infiltration areas, and riparian forests. Low-impact site design practices that limit the creation of impervious area, the compaction of natural soils, and the clearing of natural vegetation should also be applied.

Apply Absorbent Landscaping

For landscaped areas, an absorbent surface soil layer should be provided. This absorbent soil layer should:

- Be deep enough to store the mean annual rainfall (24-hour duration).

- Meet the BC Landscape Standard for medium or better landscapes, which will ensure the type of hydrologic characteristics required for rainfall capture.

Stormwater Source Control Practices

Source control options include:

- Detention systems

- Retention/infiltration systems

- Green roofs

- Rainwater reuse

Detention or Retention

It is often difficult to identify the difference between the different types of stormwater control solutions because they use much of the same equipment, such as ponds, tanks, and infiltration chambers.

Detention systems are employed on a site to reduce the quantity of stormwater runoff leaving a site by temporarily storing the runoff that exceeds a site’s allowable discharge rate and releasing or pumping it slowly over time, with little or no possibility of onsite infiltration.

The significant difference with a stormwater retention system is that it allows the water to slowly discharge into the soil instead of detaining it for a time before releasing it. This also helps to recharge the area’s water table, which is something that runoff cannot do.

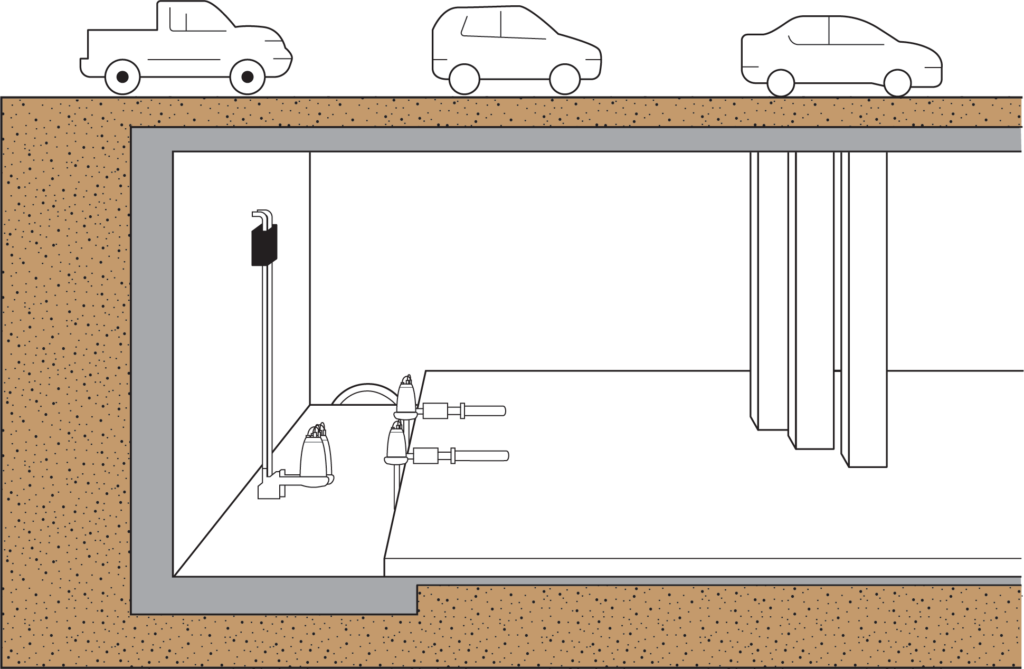

Underground stormwater retention and detention systems are a key component of reducing runoff in modern site development. Stormwater retention and detention systems are present in the industry as either above-ground ponds (Figure 1) or as subsurface storage and piping (Figure 2).

The use of ponds is the least expensive method, though it is the most inefficient use of developable land, is prone to siltation and clogging, and poses long-term aesthetic problems, such as insect breeding, weed growth, odour, and refuse issues. Whereas subsurface retention and detention systems use available land efficiently while introducing low maintenance costs and posing little or no aesthetic problems

The components of these systems typically involve underground tanks, arches, or contained pipe systems in conjunction with geo-fabrics, filters, and aggregate layers. These systems are designed to help avoid the flooding and erosion that can be caused by excess runoff. With the integrated filtration elements, the discharged water will not have an adverse effect on streams, rivers, or wetlands and all the aquatic life they support.

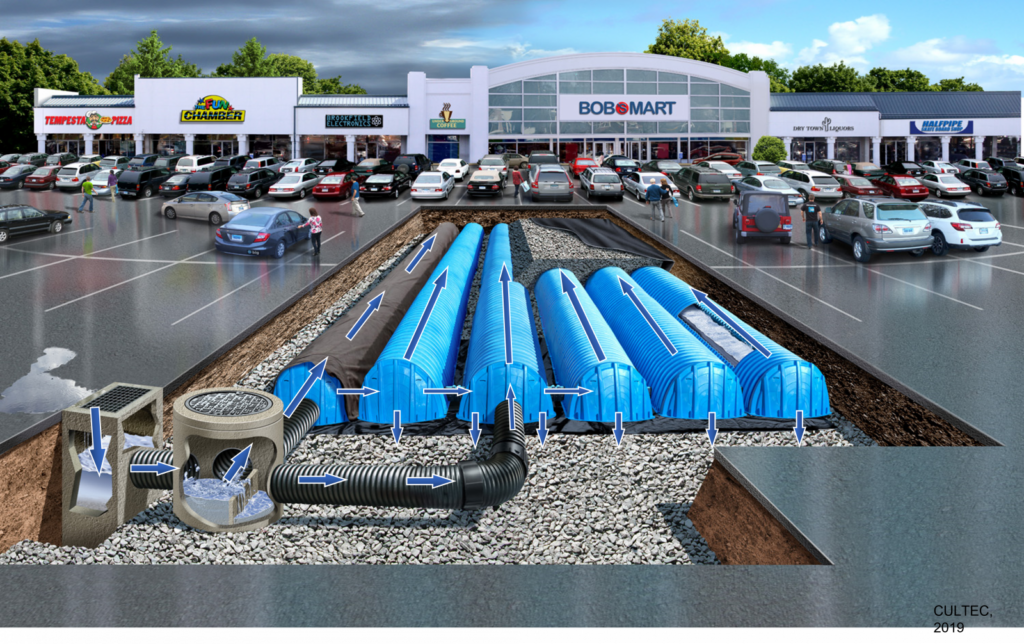

Storage infiltration systems are incorporated into a retention solution to reduce the volume of stormwater runoff being discharged from a site. The infiltration system can consist of structurally reinforced chambers (Figure 3), vaults, crates, perforated pipes, or other void-forming structures embedded in coarse aggregate.

This runoff reduction strategy is a major part of a low-impact development design. Infiltration is likely the only way to achieve the target condition of restoring 90% of total rainfall volume to natural hydrologic pathways and is the most appropriate source control for single-family land uses, which is the dominant land use in most developed watersheds in most provinces. The level of reduction in the volume and rate of runoff achievable using infiltration depends on soil conditions, and therefore, soils information is key to the planning and design of infiltration facilities.

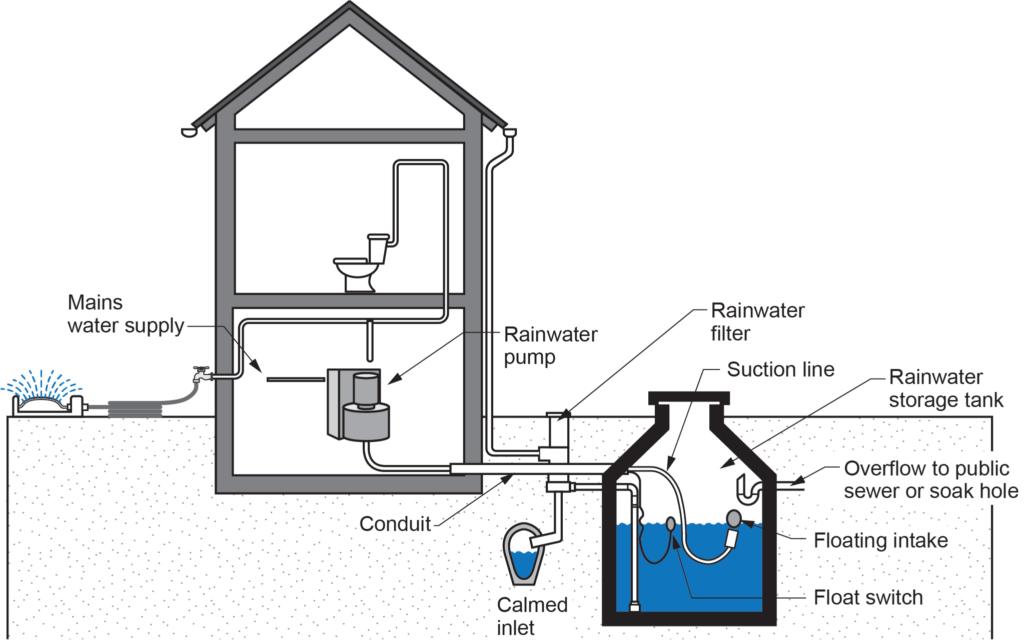

Because of the complexity of calculating target runoff discharge rates, site-retention systems for large developments (Figure 4) are typically designed by engineers and constructed by contractors to engineers’ and local authorities’ requirements. Design guidelines for systems serving single- family dwellings may be specified by local authorities due to their relatively low discharge rates. Rock pits and disposal fields, similar to those used in a septic disposal system, are most commonly used for small-scale runoff reduction. Using overflow piping to a discharge location ensures that the retention system does not back up and flood the property and equipment being served.

Green Roofs

The volume and rate of rooftop runoff can be reduced by installing absorbent landscaping on the rooftops of buildings or parkades. Green roofs (Figure 5) will store and provide evapotranspiration for rainfall from small events and will slow the rate of release of medium-sized events. Green roofs are most effective for land uses with high levels of rooftop coverage, such as multi-family and commercial land uses (especially with underground or structured parkades).

A storage layer of perforated plastic or drain rock under the green roof soil can increase the effective rainfall capture and storage volume. The drainage outflow from the green roof should be connected to infiltration facilities in suitable areas of the site with an overflow to the storm drain system. Runoff from roof water should be kept separate from paved surfaces runoff, which can be polluted with hydrocarbons and heavy metals. Whereas paved surface runoff may require treatment, most green roof runoff will be clean enough to be released directly to storage and receiving waters.

Drain inlets from green roofs will require regular inspection. Watering may be required, using either surface standard watering devices or an automatic irrigation system.

Rainwater Reuse

Capturing and reusing rooftop runoff for greywater uses (e.g., toilets and laundry) or for irrigation can reduce runoff volume. The opportunities for runoff volume reduction through reuse are most significant for high-density residential and commercial land uses with high water usage.

The benefits of rainwater reuse go beyond stormwater management in that reuse can also reduce the amount of water drawn from reservoirs and reduce the costs of water supply infrastructure.

Summary

Because there are many types of stormwater control solutions being applied in different regions, it is important to check with local building inspection departments for any regulations regarding site stormwater handling.

You can also find additional information in publications such as Storm Water Planning: A Guidebook for British Columbia.

Self-Test D-3.8: Stormwater Site Retention Systems

Self-Test D-3.8: Stormwater Site Retention Systems

Complete Self-Test D-3.8 and check your answers.

If you are using a printed copy, please find Self-Test D-3.8 and Answer Key at the end of this section. If you prefer, you can scan the QR code with your digital device to go directly to the interactive Self-Test.

References

Skilled Trades BC. (2021). Book 2: Install fixtures and appliances, install sanitary and storm drainage systems. Plumber apprenticeship program level 2 book 2 (Harmonized). Crown Publications: King’s Printer for British Columbia.

Stephens, K. A., Graham, P., & Reid, D. (2002). Stormwater planning: A guidebook for British Columba. British Columbia Ministries of Community, Aboriginal and Women’s Services and Water, Land and Air Protection. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/environment/waste-management/sewage/stormwater_planning_guidebook_for_bc.pdf

Trades Training BC. (2021). D-3: Install storm drainage systems. In: Plumber Apprenticeship Program: Level 2. Industry Training Authority, BC.

Media Attributions

All figures are used with permission from Skilled Trades BC (2021) unless otherwise noted.

- Figure 3: Arched infiltration chambers by Arbitrarily0, via Wikimedia Commons, was used by Skilled Trades BC (2021) under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license

- Figure 4: Engineered stormwater retention system by DanielFilippi, via the Sustainable Technologies Evaluation Program Wiki, is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 5: Green Roof by Sky Garden Ltd, via Wikimedia Commons was used by Skilled Trades BC (2021) under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

The continuous movement of water on, above, and below the surface of the Earth, including processes like evaporation, condensation, and precipitation. (Section D-3.7)

Water discharged from a surface as a result of rainfall or snowfall. (Section D-3.1)

Water that flows over the ground after rainfall, often because it cannot infiltrate into the soil due to impervious surfaces like pavement. (Section D-3.8)

Surfaces that do not absorb water, such as concrete, asphalt, and buildings, which increase the volume of runoff. (Section D-3.8)

Stormwater management techniques that focus on reducing runoff at its origin, such as using green roofs or rainwater capture systems. (Section D-3.8)

The process where stormwater is absorbed into the soil, reducing runoff and helping to restore the natural water balance. (Section D-3.8)

A system that temporarily stores stormwater before releasing it slowly to reduce the risk of flooding and erosion. (Section D-3.8)

A stormwater management system that allows water to be held and absorbed into the ground, reducing runoff and helping to recharge the water table. (Section D-3.8)

A rooftop covered with vegetation that absorbs rainwater, reducing runoff and providing benefits like energy efficiency and improved air quality. (Figure 5, Section D-3.8)

Water that comes from sinks, showers, and washing machines in your home. It’s not dirty like sewage water, but it’s not clean enough to drink either. Greywater can be reused for things like watering plants or flushing toilets to help save fresh water. (Section D-3.8)

The practice of collecting rainwater, particularly from rooftops, for non-potable uses such as irrigation or toilet flushing, reducing the demand on municipal water supplies and stormwater runoff. (Section D-3.8)