D-1.1 Codes and Standards

Codes and Standards

A standards organization’s primary activities are developing technical codes and standards that are intended to address the needs of the industries that adopt them. The main purpose of building codes is to protect public health, safety, and general welfare because building codes relate to the construction and occupancy of buildings and structures. A standard is a document that provides requirements, specifications, guidelines, or characteristics that can be used consistently to ensure that materials, products, processes, and services are fit for their purpose.

Standards used in the construction industry cover a range of topics but are usually in one of the following categories:

- Test or measurement standards that provide information on the acceptability (pass/fail) in a performance category, usually under some standard condition (fire separation ratings), or that provide data that can be used to determine acceptability or performance.

- Procedural standards that detail how products or systems are to be installed, used, maintained, tested, or operated to be safe, reliable, and fit for their intended use.

National Standards System

The National Standards System is the network of organizations and individuals involved in voluntary standards development, promotion, and implementation in Canada. Under the Standards Council of Canada Act, the Standards Council of Canada (SCC) is mandated with overseeing the National Standards System. The SCC is a federal non-profit Crown corporation responsible for coordinating voluntary standardization in Canada. It is also responsible for Canada’s activities in voluntary international standardization.

Canadian Standards

Plumbing codes contain many references to standards published by accredited standards development organizations in Canada. As part of the accreditation requirements, these organizations adhere to the principles of consensus. This generally means substantial majority agreement of a committee — comprising a balance of producer, user, and general-interest members — and the consideration of all negative comments. The organizations also have formal procedures for the second-level review of the technical preparation and balloting of standards prepared under their auspices. The Canadian Commission on Building and Fire Codes (CCBFC) follows these same principles of consensus in the operation of its code development process.

The following organizations are accredited as standards development organizations in Canada:

- American Society for Testing and Materials International (ASTM)

- Bureau de normalisation du Quebec (BNQ)

- Canadian General Standards Board (CGSB)

- Canadian Standards Association (CSA)

- ULC Standards (ULC)

- Underwriters’ Laboratories (UL)

Non-Canadian Standards

A number of subject areas for which the Canadian standards development organizations have not developed standards are covered in the National Plumbing Code of Canada. In these cases, the code often references standards developed by organizations in other countries, such as the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE), and the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA). These standards are developed using processes that may differ from those used by the Canadian standards development organizations; nevertheless, these standards have been reviewed by the relevant standing committees and were found to be acceptable.

Certifications

Products are considered “listed” or “approved” when they have been tested and certified by an accredited certification organization. They appear in a list of certified products in either an electronic or hard copy directory published by that organization. Testing and certification involves an initial independent, third-party evaluation of a product to determine if the product conforms to applicable standards.

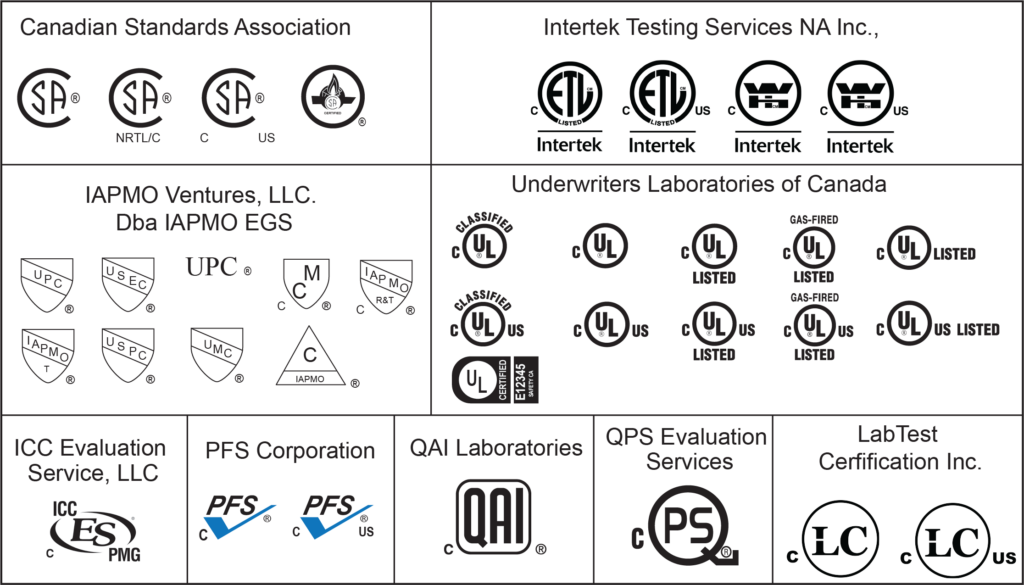

The following certification organizations have been accredited to test/certify plumbing products for Canada: BNQ, IAPMO, ICC, LabTest, NSF, QAI, UL & ULC, and the Water Quality Association (Figure 1). Products that do not bear one of the following marks may not be appropriate for sale and installation in all jurisdictions and, in some cases, may create health and safety issues.

Each organization’s scope of accreditation and certification marks can also be accessed at the Standards Council of Canada (SCC).

A certified product is required to bear the certification mark. Some fixture manufacturers acknowledge that customers want an mark-free aesthetic and choose to mark their product with a permanent adhesive label designed to be removed after inspection and that will also self-destruct so that it cannot be placed on another product. If an adhesive label is accidentally removed prior to inspection, the inspector has no choice but to assume that the product is uncertified and request its removal. Therefore, it is important that contractors and consumers maintain proof of the product certification compliance on the product (in addition to the carton, installation instructions, warranty and homeowner’s manual, and specification sheet) until after inspection.

Government Roles in Code Enforcement

Provincial and territorial authorities with jurisdiction are responsible for:

- Adopting and enforcing laws and regulations

- Providing interpretation of these laws and regulations

- Providing training and education

- Establishing roles and responsibilities of trades people and professionals

Local Government Systems in BC

BC’s local government system is unique in Canada, accommodating diverse local governance structures within a federated model that provides local services and governance to communities throughout BC. One hundred and 62 municipalities and 27 regional districts serve urban and rural communities in virtually all areas of BC.

The first municipalities predate the establishment of British Columbia as a province. Regional districts were created in the mid-1960s. Other local service bodies, such as improvement districts (not local governments), continue to exist in some areas.

Municipalities in BC

Municipalities in BC are responsible for providing local services and governance to approximately 89% of the province’s population. There are currently 162 municipalities, ranging in population from just over 100 to over 630,000 people and ranging in size from 63 hectares to over 8,500,000 hectares.

Municipalities can be classified as either a town, village, district, or city, depending on the size and density of their population. An older classification, township, is still referenced in the names of some municipalities; townships are currently classified as districts. Municipalities were first established in BC in the late 1800s. Since then, the roles and responsibilities of municipalities have evolved to become more complex. The BC government sets the legislation that provides municipalities with the authority and flexibility to respond to the varying needs and changing circumstances of each community. Within that framework, the BC government regards municipalities as autonomous, responsible, and accountable governments directed by democratically elected councils.

Most municipalities are incorporated by the BC government through the issuance of a legal document called a letters patent. Each letters patent contains the name of the municipality, describes or represents its boundary, and establishes its classification. Early municipalities were incorporated by the colonial or provincial legislature under legislative acts, although the power to create new municipalities in response to local interest was granted to the Provincial Cabinet in 1910.

The City of Vancouver is an enduring example of a municipality created and operating under a distinct piece of legislation (Vancouver Charter). On rare occasions, a municipality has also been created by special legislation, such as the City of Powell River and the Resort Municipality of Whistler.

Municipal Powers

Core municipal powers and responsibilities are set out in the Local Government Act and Community Charter. For the City of Vancouver, its key powers and responsibilities are set out in the Vancouver Charter. Other legislation may also provide important authorities or requirements for municipalities, including the Motor Vehicle Act, Environmental Management Act, and the Building Act.

Municipalities generally have some of the broadest service authorities in Canada to provide whichever services they consider necessary or desirable for the community. Municipalities may provide services directly or indirectly — for example, through the regional district, with a private partner, or with another government. Municipalities are not responsible for schools, social assistance, or hospitals. These are a provincial responsibility exercised directly or through other bodies.

Municipal Bylaws

Municipal councils and regional district boards may only make decisions by bylaw or resolution. Bylaws are laws that formalize rules made by a council or board. Local governments may use bylaws for various purposes, especially to regulate, prohibit, or impose requirements. Local bylaws will require you to apply for building and plumbing permits, for example.

Bylaws are laws passed by municipal councils and regional district boards to exercise their statutory authority. Bylaws may be used for a variety of different purposes, including:

- Establishing meeting procedures

- Regulating services

- Prohibiting an activity

- Requiring certain actions

Bylaws and the Building Act

The Community Charter of BC states that municipalities are “… subject to any specific conditions and restrictions established under this or another Act” and that “a provision of a municipal bylaw has no effect if it is inconsistent with a Provincial enactment.”

The Building Act of BC (enacted 2015) also states that “… a local building requirement … has no effect to the extent that it relates to a matter that is subject to a requirement, in respect of building activities, of a (provincial) building regulation.…”

Prior to the Building Act, local governments had the authority to set technical building requirements in their bylaws that differed from those set by the province in the BC Building Code. To bring greater consistency to the technical building requirements in force across BC, the Building Act gives the province sole authority to establish these requirements.

Under Section 5 of the Building Act, if a matter is regulated in a provincial building regulation, any requirements for that matter established in bylaws by local governments will be of no legal force after December 15, 2017.

When a provincial building regulation does not regulate a matter (e.g., requirements relating to fencing or erecting a freestanding sign), local governments may regulate such matters if they determine they have legislative authority to do so.

Basically, this means that local bylaws cannot supersede the requirements of building codes.

Note that the Building Act does not apply to the city of Vancouver. Under the Vancouver Charter, Vancouver has authority to set its own building requirements through bylaw and to determine the qualification requirements for the city’s building officials. It also has its own appeal process for building bylaw disputes.

Permits

Depending on the scope of the work you are proposing, you may also need a building permit, development permit, or both.

Building Permits

You will need a building permit if you plan to:

- Construct a new building

- Make any addition to an existing building

- Alter the structure of a building

- Renovate, repair, or add to a building

- Demolish or remove all or a portion of a building

- Change a building’s use

- Build a garage, balcony, or deck

- Excavate a basement or construct a foundation

Plumbing Permits

Plumbing permits are required for the construction of all associated systems and must be obtained before construction begins.

A plumbing permit is required if you want to:

- Install, change, or upgrade any part of a plumbing system

- Do repair or replacement work if you have to:

- Open walls

- Move pipes

- Change other plumbing or pipes

If your company is a licensed gas contractor, you will require a gas permit to install or replace a gas-fired appliance, such as a fireplace, hot water tank, boiler, furnace, or kitchen stove. A permit is also required if you are installing or altering the associated gas pipes and appliance vents.

If you are constructing a new dwelling, you will require a building permit prior to being issued a gas or plumbing permit. A plumbing permit is NOT required for clearing stoppages or repairing leaks in pipes, valves, or fixtures.

Plumbing permits are issued by your local municipal building department. Gas permits are typically issued by Technical Safety BC. In some instances, gas installation permits might also be offered by municipal departments.

The permit process is generally the same for all types of projects, but there may be more specific requirements for some commercial construction and industrial projects.

Permit Application

A completed permit application is required prior to beginning the permit-issuing process. Permit applications are available through the authority having jurisdiction (AHJ). Typical required information includes who will perform the work and what, where, and how the work will be completed. Drawings, plans, or other documentation of the proposed work may be required. Permit fees are usually due at the time of application.

Review Process

During the review process, staff determine if the project is in compliance with the applicable codes and other local ordinances and statutes. The length of the review process depends on the type and complexity of the project. Many small residential applications can be processed in one day.

Permit Approval

When compliance with the code and other applicable statutes is determined, the permit application is approved. Once all final permit fees are paid, the permit is issued.

However, if the permit application is not approved or a review has failed, the permit application as submitted will be denied. When a permit application is denied, corrections to the application shall be made and the application is resubmitted for final approval.

Permit Execution

There are various stages involved in executing any building permit.

Construction

During the entire construction phase, the permits must be placed in a prominent place at the project site. A copy of the approved building plan and other related documents must also be maintained at the site.

Inspections

Each major phase of construction must typically be inspected by an inspector or similar authority to ensure that the work conforms to the code, permit, and approved plans. Inspection requests may be made via internet, by phone, or in person. Normally, the response is one business day after the request is made.

Field Changes

Most changes will require a review and approval in the same manner as the original application. Proposed revisions or alterations must be brought to the attention of the permit staff before making changes in the field.

Project Completion

When the project is completed and code compliance is determined, the inspector issues a final inspection. The final inspection marks the completion of the project and grants permission to occupy a building with the knowledge that it has met the minimum safety standards as required by the code.

Plumbing Codes

The BC Plumbing Code (BCPC) is the standard for the province of BC and has historically been substantially based on the National Plumbing Code (NPC) of Canada.

The NPC was developed by the National Research Council with collaboration from provinces and territories. The National Codes are updated approximately every five years. The NPC is a model code in the sense that it helps promote consistency among provincial and territorial plumbing codes.

In Canada, provincial and territorial governments have the authority to enact legislation that regulates the design and installation of plumbing systems within their jurisdictions. This legislation may include adopting the NPC without change or with modifications to suit local needs and enacting other laws and regulations regarding plumbing system design and installation, including the requirements for professional involvement. People involved in designing or installing plumbing systems should consult the provincial or territorial government with jurisdiction to find out which plumbing code is applicable

In the past, BC has produced an updated consolidated BCPC to reflect NPC updates and any unique provincial needs. Over time, these two codes have become harmonized to the point that, in 2024, the province of BC announced they would adopt the NPC rather than produce a separate BCPC.

The BC Information Bulletin stated that as of March 8, 2024, “The British Columbia Building Code 2024 Book I (General) (Building Code) adopts the British Columbia Building Code Book II (Plumbing Systems) by reference in Part 7 of Division B, it also effectively states that the British Columbia Building Code 2024 Book II (Plumbing Systems) is the National Plumbing Code of Canada 2020″ (NPC 2020).

Plumbing code users will follow the provisions relevant to plumbing systems in the BC Building Code, such as Part 1 of Division A and Part 7 of Division B, together with the NPC. This means that even though provincial documents — and this textbook — may still refer to the relevant plumbing code as the BCPC, the official document is essentially the NPC. The electronic versions of the BC Codes are available on the BC Codes website.

The NPC sets out technical provisions for designing and installing new plumbing systems. It also applies to the extension, alteration, renewal, and repair of existing plumbing systems. The NPC establishes requirements to address the following four objectives, which are fully described in Division A of the code:

- Safety

- Health

- Protection of buildings and facilities from water and sewage damage

- Environment

The NPC is not a textbook on plumbing system design or installation. The design of a technically sound plumbing system depends upon many factors beyond simple compliance with plumbing regulations. Such factors include the availability of knowledgeable practitioners who have received appropriate education, training, and experience and who have some degree of familiarity with the principles of good plumbing practice and experience using textbooks, reference manuals, and technical guides.

The NCPC provides the minimum requirements for:

- Drainage systems for water-borne wastes and storm water for buildings to the point of connection with public services,

- Venting systems

- Water service pipes

- Water distribution systems

The NPC does not list acceptable proprietary plumbing products. It establishes the criteria that plumbing materials, products, and assemblies must meet. Some of these criteria are explicitly stated in the NPC, while others are incorporated by reference to material or product standards published by standards development organizations.

Numbering System

A consistent numbering system has been used throughout codes in Canada: The first number indicates the part of the code; the second is the section in the part; the third is the subsection; the fourth is the article in the subsection; and so on. The detailed provisions are found at the sentence level (indicated by numbers in brackets), and sentences may be broken down into clauses and subclauses. This structure is illustrated in Table 1.

| Number | Category | Example |

|---|---|---|

| 1st | Part | 3. |

| 2nd | Section | 3.5. |

| 3rd | Subsection | 3.5.2 |

| 4th | Article | 3.5.2.1. |

| 5th | Sentence | 3.5.2.1.(2) |

| 6th | Clause | 3.5.2.1.(2)(a) |

| 7th | Subclause | 3.5.2.1.(2)(a)(i) |

Change Indication

Where a technical change or addition has been made relative to a new edition, a vertical line has been added in the margin next to the affected provision to indicate the approximate location of new or modified content. No change indication is provided for renumbered or deleted content.

Wastewater Treatment and Disposal

Wastewater is approximately 99% water. The remainder is composed of a mix of organic wastes, detergents, cleaning chemicals, and anything else poured or flushed down indoor drains. Wastewater contains chemicals and micro-organisms that can threaten public health and damage the environment.

A building permit cannot be issued unless the building is connected to a public or private onsite sewage system.

Onsite Sewage Systems

Onsite sewage systems are installed in areas that are not served by a public sanitary sewer network. Onsite sewage systems are effective at treating household sewage if they are designed and installed properly in appropriate soil and maintained regularly. In typical onsite sewage systems, the wastewater from toilets and other drains flows from your house into a tank that separates the solids and scum from the liquid. Bacteria help break down the solids into sludge. The liquid flows out of the tank into a network of pipes buried in a disposal field of gravel and soil. Holes in the pipes allow the wastewater to be released into the disposal field. These systems can be efficient and cost-effective and can protect health and the environment. However, they must be properly planned, installed, and, above all, properly maintained.

Enacted in 2005, the Sewerage System Regulation (SSR) applies to all smaller systems, including those for houses, small businesses, and even small community systems. Compared to the previous Sewage Disposal Regulation, the SSR includes a significant change in approach. The new approach is performance-based, and responsibility for the proper design and installation of onsite systems has been transferred for the most part from health authorities to “authorized persons,” as defined by the SSR.

BC Sewerage System Regulation

The Sewerage System Regulation replaced the old Sewage Disposal Regulation. This regulation — along with the companion document, the Sewerage System Standard Practice Manual — shifted the focus of managing onsite sewerage systems by using an outcome-based approach to wastewater management to allow for greater flexibility in how the systems are regulated.

An onsite sewerage system is usually located on the land from which sewage originates. This type of system locally treats effluent that is not serviced by a larger municipal or regional sewerage system.

The Sewerage System Regulation, under the Public Health Act, covers holding tanks for sewage effluent or onsite sewerage systems that:

- Process a sewage flow of less than 22,700 L per day

- Serve single-family systems or duplexes

- Serve different buildings on a single parcel of land

- Serve one or more parcels on strata lots or on a shared interest of land

The regional health authorities are responsible for accepting applications and fees for onsite sewerage systems submitted by homeowners or by industry professionals acting on their behalf. Authorized people install, repair, and maintain onsite sewerage systems.

Site investigations of sewerage systems may be initiated in cases where systems are suspected to be negatively affecting a drinking water supply (e.g., as a result of system failure) or causing a health hazard, as per the Public Health Act.

Agencies and Organizations

Wastewater is regulated by two provincial agencies:

- The Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Strategy: regulates large community wastewater systems under the Environmental Management Act and the Municipal Wastewater Regulation.

- The Ministry of Health: regulates smaller, generally private, domestic sewerage systems, including on-site septic systems, under the Public Health Act and the Sewerage System Regulation.

There are a number of associations that support the wastewater treatment and disposal industry:

- BC Onsite Sewage Association (BCOSSA) and Western Canada Onsite Wastewater Management Association (WCOWMA): develop educational programs for onsite wastewater practitioners and provide technical information to industry stakeholders and practitioners.

- Applied Science Technologists and Technicians of BC (ASTTBC): the association for technology professionals in British Columbia. The ASTTBC also registers practitioners once they have obtained the proper training.

- Association of Professional Engineers and Geoscientists of British Columbia (APEGBC): the licensing body for professional engineers and geoscientists. Only professional engineers and geoscientists are permitted to construct and/or maintain a Type 3 sewerage system.

- BC Water and Waste Association (BCWWA): supports over 3,700 water and wastewater professionals in BC and the Yukon with training, educational opportunities, technology transfer, and networking opportunities.

- Onsite Wastewater Registration Program (ASTTBC): provides information for onsite wastewater service providers.

Self-Test D-1.1: Codes and Standards

Self-Test D-1.1: Codes and Standards

Complete Self-Test D-1.1 and check your answers.

If you are using a printed copy, please find Self-Test D-1.1 and Answer Key at the end of this section. If you prefer, you can scan the QR code with your digital device to go directly to the interactive Self-Test.

References

Government of British Columbia. (2024). British Columbia Building Codes. https://www.bccodes.ca/index.html

Skilled Trades BC. (2021). Book 2: Install fixtures and appliances, install sanitary and storm drainage systems. Plumber apprenticeship program level 2 book 2 (Harmonized). Crown Publications: King’s Printer for British Columbia.

Standards Council of Canada. (n.d.). Accreditation. https://scc-ccn.ca/accreditation

Trades Training BC. (2021). D-1: Install sanitary drain, water and vent systems. In: Plumber Apprenticeship Program: Level 2. Industry Training Authority, BC.

Media Attribution

- Figure 1 CSA B149.1:20, Natural gas and propane installation code. ©2020 Canadian Standards Association. (Please visit store.csagroup.org)

Rules that explain how to check if something is the right size, strength, or quality. These standards make sure that tests are done the same way every time so results can be trusted and compared. (Section D-1.1)

Step-by-step rules that explain how to do a plumbing job correctly and safely. These standards make sure that everyone follows the same process when installing or fixing plumbing systems.

The plumbing standard for British Columbia, historically based on the National Plumbing Code of Canada. (Section D-1.1)

BC regulation governing the design, installation, and maintenance of onsite sewage systems. (Section D-1.1)

See "Sewerage System Regulation" (Section D-1.1)